A nonprofit organization founded to end excessive use of force by police is calling on the public to demand that all language in police union contracts related to discipline be removed. It is also calling for more community oversight of police discipline.

One of Campaign Zero’s major platforms, at a time of continued public protests over police brutality, is to stop police unions from interfering in disciplinary matters when officers are investigated for excessive use of force and other police misconduct.

So far, it has found successes and challenges in this pursuit.

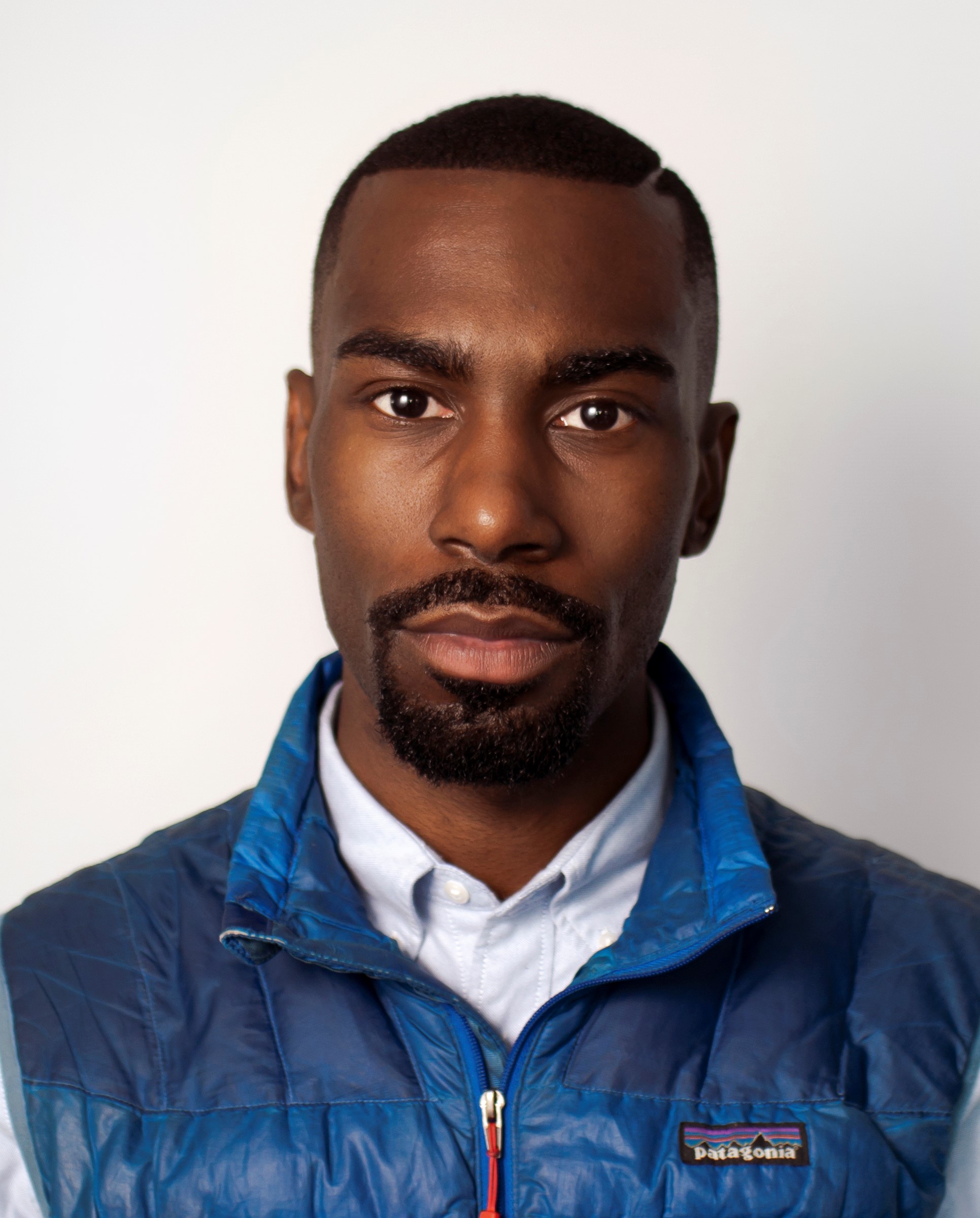

“We are working now in 15 cities to help them strategize, working with organizers in the cities,” said DeRay McKesson, a protester and co-founder of Campaign Zero. “There is a different strategy for each city because every contract is different. We work for city-specific strategies around the goals of Nix the 6.”

RELATED: Use of force by police gets more scrutiny

RELATED: Resignations mount as calls for police reform get louder

Nix the 6 is “a national platform of data-driven policy solutions to end police violence in America.” It focuses on the six top ways these protesters believe police unions obstruct, delay or defeat local efforts to hold police accountable. It also focuses on reimagining public safety.

The six categories are:

- Police union contracts blocking accountability

- Rehiring officers fired for misconduct

- Police Bill of Rights laws

- Union influence over police budgets

- Police unions buying political power

- Negotiations without community representation

Campaign Zero says police unions and union contracts are major barriers to defunding or abolishing police departments across the country. In many cities, these contracts limit the city’s ability to move money or reduce staff and automatically increase personnel costs – typically 80% of the police budget. Many contracts also restrict which department roles can be eliminated or reassigned to alternative responders, such as social workers or mental health professionals.

The Police Foundation, which works to build police legitimacy through measuring and managing performance, did not return calls to The Legal Examiner to comment for this article.

Campaign Zero launched The Police Union Contract Project in 2015, the first public database of police union contracts and police bill of rights laws, documenting the ways in which these contracts and laws make it harder to hold police accountable.

“Since then, we’ve worked with organizers in cities across the country to renegotiate these contracts, challenge these laws, and repeal language that blocks police from being held accountable for misconduct,” the Campaign Zero website states. “#NixThe6 expands upon this work by publishing new analyses of nearly 600 cities’ police union contracts and encouraging specific policy and legislative actions to address these issues.”

“We did a big FOIA (Freedom of Information request) for union contracts, got them, analyzed them and coded the six categories,” McKesson said. “They are the deciders of how discipline happens, how the process leading up to discipline happens.”

Campaign Zero started this effort in 2015 with 100 cities and obtained 80 union contracts in some of the nation’s largest cities. “We were trying to understand better, structurally, why officers were never held accountable” for excessive force and other misconduct. Details in these contracts matter, he said.

“We started in Austin a couple of years ago. The city council voted unanimously against the union contract” then went to work through a negotiating team. “There are some places where six are a problem and some where two are a problem,” McKesson said. “Every city has a different approach and plan. In Austin, we rolled out Nix the 6 with the underlying six buckets, but they worded it differently. They got what they wanted, seven of the eight things they listed as issues. It was a huge win.”

The contract, approved in 2018, was just over half the monetary amount of the original contract the city rejected, according to The Statesman. “The $44.6 million contract was approved unanimously by the council and by about 80 percent of the union’s voters. Thursday’s votes came nearly a year after the council rejected a previous $82 million, five-year contract proposal because of its high price tag, setting off a months-long debate among city leaders, police officials, community activists and the union on what sort of agreement would best serve the city — and leaving many officers discontented while they waited.”

In exchange for the pay increases, which were less than previously requested, the city created an Office of Police Oversight to replace the Office of the Police Monitor. It will expand the role and powers of the previous office as it takes complaints against police officers and reviews cases, The Statesman reported.

“The office will now conduct random assessments of body-worn camera footage and use-of-force cases, and it will have slightly expanded powers to publish case information,” the article states. “Last year, community activists rallied against the previously proposed contract and what they saw as a lack of accountability and oversight of the police department.”

The Austin changes are the kind Campaign Zero promotes, McKesson said, which allows more oversight by the community and less power by the unions.

Police union contracts typically contain language that blocks officer accountability for using brutal policing methods, the group believes. They say unions are responsible for destroying records of past misconduct and disqualifying new complaints of misconduct that may result in discipline.

“We must demand cities remove all matters of investigations, discipline, and records retention from the police union contracts,” its website states. “For example, Washington, D.C.’s council just passed legislation removing all disciplinary matters from the scope of police union contract negotiations — making police accountability non-negotiable.”

But that battle is not over, according to an August article in the Washington Post. “The union representing D.C. police officers sued the District in federal court…, challenging a new law that makes it easier for the police chief to discipline and fire officers by cutting out the role of the labor group. In its suit, the union said the District unfairly created a ‘distinct class’ of government employees and called it discriminatory to strip the officers’ labor representatives of the ability to help shape the disciplinary process, as is afforded to nearly all other District workers.”

“The DC Police Union has always been steadfastly committed to having important discussions on police reform,” the union stated in a news release. “We support many of the measures in the new police reform law and, in fact, believe some of them could even be expanded. Unfortunately, our efforts to be involved in the process of creating new legislation has been thwarted by the ‘emergency’ nature of the law and the council members’ obvious aversion to including the voices of the 3,600 rank-and-file police officers in their deliberations on these subjects.”