In the ongoing effort to reverse the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court “Citizens United’’ ruling regarding campaign finance from Super PACs, members of Congress recently introduced the Democracy for All amendment that would allow states and Congress to pass legislation imposing spending limits. With Democrats now in control in the U.S. House and Senate, there’s an increased chance of movement for the Democracy for All amendment.

The amendment first introduced in 2014 hasn't gained much traction, but it’s a slow and steady process to add an amendment to the Constitution. First it must pass in Congress by a two-thirds margin and then three-fourths of state legislatures must approve the amendment. The 27th amendment took about 200 years to be ratified and the Equal Rights Amendment has yet to become law.

RELATED: Equal Rights Amendment lies in legal limbo, as decades of debate continue

RELATED: Biden has big plans, and many challenges, for immigration reform

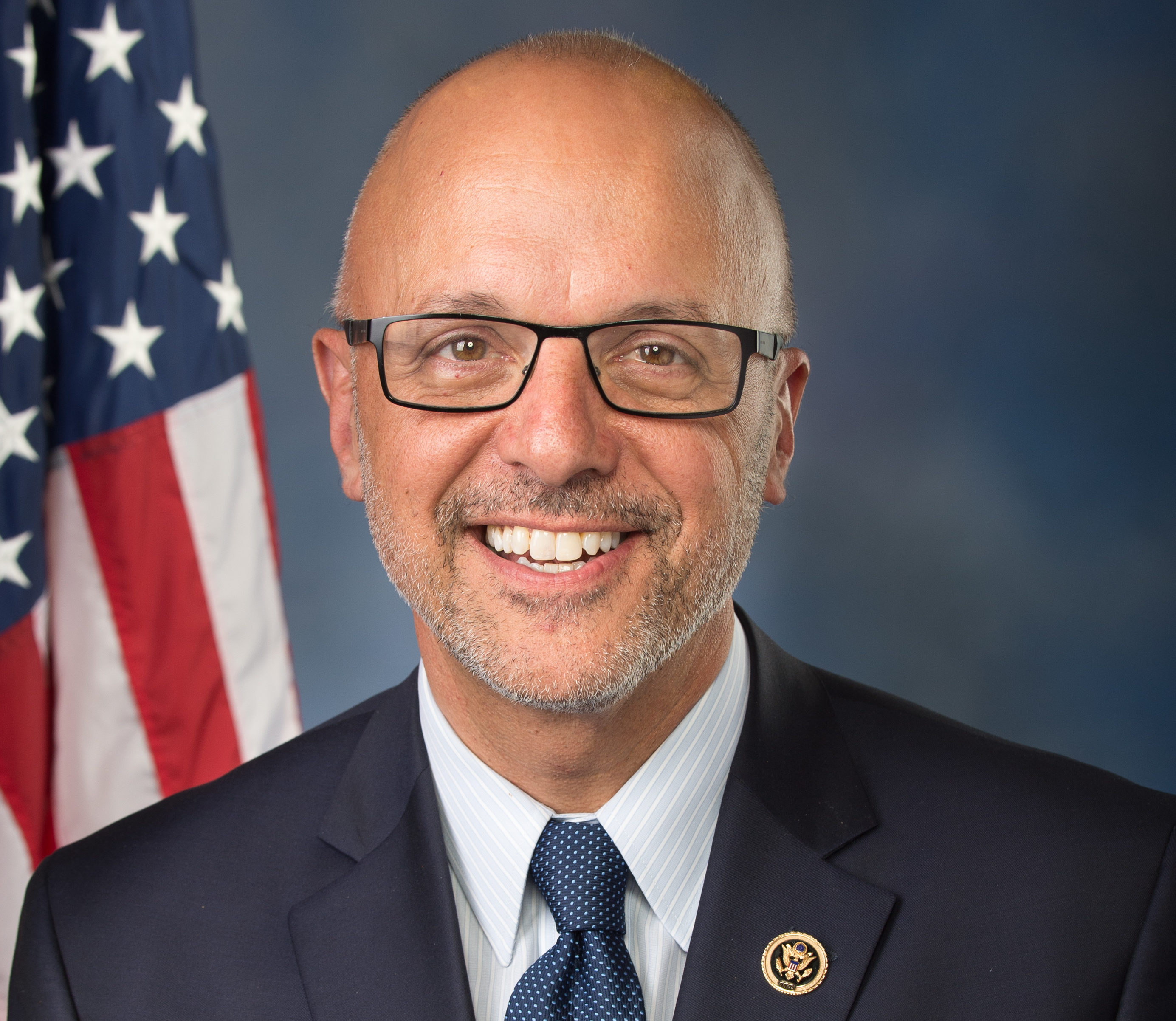

“Democratic leaders in both chambers have made repairing our democracy a top priority, and we are still working toward two-thirds support for this amendment to overturn Citizens United,” said Rep. Ted Deutch, D-FL, a co-sponsor who recently reintroduced the amendment. “As I continue to build support for the amendment, I am confident we will get the For The People Act to President Biden’s desk to make it easier for Americans to vote, bring more disclosure to political spending, and crack down on corruption. The legislation has important provisions to require disclosure of political funders and reduce corruption.”

Impacts of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission

In the 2010 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that limiting “independent political spending” from corporations and other groups violates the First Amendment right to free speech. The majority of the court believed independent political spending, separate from a candidate’s campaign spending, didn’t present a threat of corruption as long as the independent party didn’t coordinate with the candidate or their campaign. In the decade since, it has become clear that it is hard to ensure there is no coordination.

The court also believed because donors to Super PACs were public information, there would be transparency of the unlimited money given to these political organizations.

Super PACs must report their donors to the Federal Elections Commission, but the Citizens United ruling that allows unlimited donations to outside PACs opened the door to millions of dollars financing ads and other campaign resources without any public knowledge of the source of the money.

“Dark money becomes dark when it goes through an opaque nonprofit like a 501(c)(4) or 501(c)(6). Thus, if you wanted to hide corporate political spending then the corporation gives to 501(c)(6) and the 501(c)(6) gives to the Super PAC,” said Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, a professor at Stetson University College of Law teaching Election Law and Constitutional Law. “All the public will see is the donation from the 501(c)(6) to the super PAC. The public cannot see that the corporation is the true source of the money.”

Super PACS have raised more than $8 billion that went toward influencing campaigns since Citizens United, according to the Brennan Center For Justice, a nonpartisan law and policy institute at New York University School of Law.

“As of 2018, roughly $1 billion had come from just 11 people. Dark money groups that keep their donors secret, but which we know are funded by many of the same donors who back Super PACs, have spent well over $1 billion more. Overall, in the decade since Citizens United, donors who give more than $100,000 have come to dominate federal campaign fundraising,” an article on the Brennan Center’s website stated last month.

“The (Democracy For All) amendment would overturn Citizens United, but that doesn’t mean that spending limits would immediately take effect. The Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United was wrong because the majority said spending by independent groups that are not coordinated with campaigns does not risk corrupting our elections and that corruption could be mitigated through disclosure,” Deutch said. “Unfortunately, coordination rules have not been enforced, disclosure requirements can be circumvented using tax-exempt dark money groups, and billion-dollar elections allow wealthy special interests to elevate themselves above the national interest.”

While this kind of money and influence clearly undercuts the millions of average voters who one would think would want to rally to change campaign finance laws, it’s not such an easy sell.

“Voters care about this stuff, but I think it’s hard to get it anywhere near their top priority,” said Abby Wood, Associate Professor of Law, Political Science and Public Policy at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law. “We want substantive policies that tend to the garden of our democracy. That’s less enticing to think about, but it is pretty important foundational stuff. This is hard stuff to make the voters care about when they are worried about really basic stuff like minimum wage or really urgent stuff like climate change.”

For The People Act

Deutch points to the For the People Act, the first legislation proposed by the Democratic party in both chambers this year, as a measure that could help counteract some complaints of the Citizens United ruling, before his amendment passes.

Under the bill, congressional candidates who agree to take no more than $1,000 from any contributor and spend no more than $50,000 of their own money qualify for public money to match donors’ funds given to candidates in small amounts. Donations to participating House and Senate candidates of $1 to $200 would be matched at a six-to-one ratio.

The act also creates a pilot program to provide eligible donors with $25 in “My Voice Vouchers” to give to congressional candidates of their choice in increments of $5. Such a voucher program has proven successful in Seattle while the public funds for matching small donations has taken place in New York City.

The For the People Act also closes legal loopholes by requiring all groups that spend significant money on campaigns to disclose the donors who are funding that spending. It also expands disclosure requirements to apply to online campaign ads on the same terms as those run on more traditional media.

There are also tighter restrictions on the coordination between candidates and outside groups that are allowed donations of unlimited amounts.