To Tony Lombardo, who has multiple sclerosis, the Americans with Disabilities Act bestowed recognition of disabled people’s basic humanity.

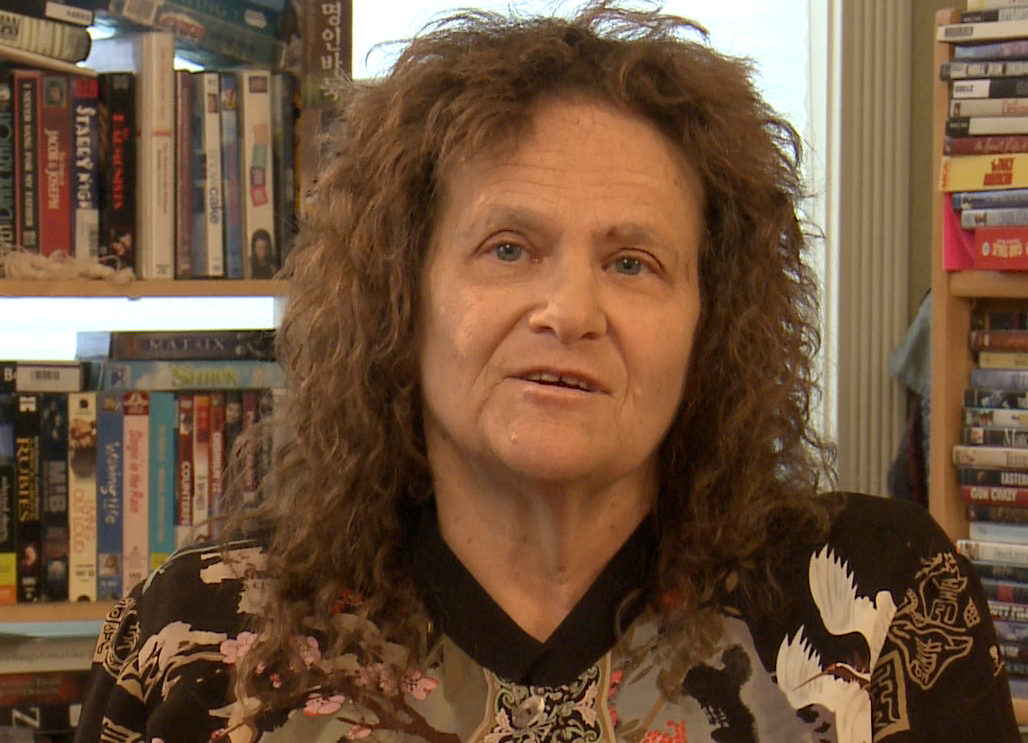

Marilyn Golden, who uses a wheelchair, says life under the ADA is “hugely different, but it doesn’t mean it’s enough.”

And John Morris, who also uses a wheelchair and has a website for wheelchair travelers, thinks the law has opened up access in a lot of places where it didn’t previously exist, but has not lived up to its full potential.

As the landmark civil rights law turns 30 years old, advocates, disabled individuals and researchers are evaluating the impact it has had across a variety of fronts, from transportation to public accommodations, from communications to employment.

In some very literal ways, the law has transformed the landscape, from the ubiquity of curb cuts to the appearance of ramps and elevators where stairs once stood alone as virtually insurmountable barriers to people who use wheelchairs.

But while experts agree the law has done profound good, its overall report card is mixed.

Public buildings and transportation are generally more accessible to people with disabilities, but not every city and business has changed.

And the law’s effect on employment for disabled individuals has, so far, not been apparent. However, signs are emerging that it may yet help them to get and keep jobs, especially as the law’s effects on educational opportunities begin to bear fruit.

Overall, some say frustrations remain for those trying to navigate the system and ensure their rights.

RELATED: Currently under siege, whistleblowers date back to our founding

RELATED: Florida criminalizes fake emotional support animal ownership

Before the ADA, disabled people faced “widespread, systemic, inhumane discrimination”

Still, the U.S. is a much different place now for people with disabilities than it was before the ADA was enacted.

Disability rights scholar and legal advocate Robert L. Burgdorf Jr. described the U.S. before the ADA in a Washington Post article five years ago as a place of “widespread, systemic, inhumane discrimination against people with disabilities.”

Millions of children, he wrote, were either excluded from schools altogether or not provided services to meet their basic educational needs.

“State residential treatment institutions for people with disabilities were generally abysmal,” he wrote. “Large state facilities, typically located in rural areas with high walls and locked wards that isolated the residents from the rest of society, were primitive and often unsanitary, dangerous, overcrowded and inhumane.”

Public and private transportation, as well as public buildings and businesses made almost no accommodations for people with disabilities, he added. “Curb cuts or ramps on sidewalks were extremely rare, often forcing people who used wheelchairs to make their way on streets, where they faced the peril of being hit by motor vehicles.”

And perhaps most appallingly, Burgdorf wrote that, “Several U.S. cities, including Chicago, Columbus and Omaha, had what became known as ‘ugly laws’ that banned from streets and public places people whose physical condition or appearance rendered them unpleasant for other people to see. These laws were actually enforced as recently as 1974, when a police officer arrested a man for violating Omaha’s ordinance.”

Law provides “basic guarantees”

Burgdorf just launched a new website telling his story and the story of the ADA. He says now that the law has, in many ways, “lived up to the high hopes that accompanied its passage.”

The law was signed by President George H.W. Bush on July 26, 1990.

“This Act is powerful in its simplicity,” the president said at the time. “It will ensure that people with disabilities are given the basic guarantees for which they have worked so long and so hard. Independence, freedom of choice, control of their own lives, the opportunity to blend fully and equally into the rich mosaic of the American mainstream.”

For the first time, people with disabilities were given legal protection from discrimination. No longer would it be acceptable under U.S. law to deny people with disabilities the right to travel, live and work freely because of their disabilities.

Among the law’s specific provisions:

- Businesses with 15 or more employees are prohibited from discriminating in hiring, recruitment, promotions, training, pay, social activities and other privileges of employment. It restricts questions that can be asked about a disability before a job offer and it requires employers to make reasonable accommodations to the known physical or mental limitations of otherwise qualified individuals with disabilities, unless such accommodations result in undue hardship.

- State and local governments are required to give people with disabilities an equal opportunity to benefit from government programs and services. They are also required to follow standards in making their buildings accessible and communicate effectively with people who have hearing, vision or speech disabilities.

- Public transportation services are barred from discriminating against people with disabilities. When purchasing new vehicles, they must comply with standards for accessibility.

- Businesses or nonprofit service providers that accommodate the public, such as hotels, movie theaters, private schools and sports stadiums, must comply with basic nondiscrimination requirements that prohibit exclusion, segregation and unequal treatment.

The law has been interpreted and enforced by the courts, not always with the desired results. After a series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions severely limited the law’s application, Congress adopted revisions in 2008 that expanded the law’s definitions to restore its strength.

The ADA established the U.S. as a world leader, but politics limited its participation

The ADA was the first of its kind in the world and established the U.S. as a leader in disability rights. Other countries have based their laws on the ADA model, and it was the basis for an international treaty adopted at the United Nations in 2008, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

But the U.S. never fully signed on to the treaty. While President Barack Obama signed it, the U.S. Senate failed to ratify it.

“It’s embarrassing,” said law professor Robert Dinerstein. “181 countries have ratified it. We have not. We have a resistance to ratifying human rights treaties, not just this one. It’s outrageous.”

Enforcement in the courts

As with other civil rights laws, enforcement of ADA’s provisions is primarily through litigation brought by individuals who face discrimination. Though the federal government does investigate and sue some larger entities, most day-to-day discrimination is not addressed by the government.

As a rule, federal courts tend to be more pro-business than they are pro-employee, said Dinerstein, who is acting dean and law professor at American University Washington College of Law.

On the other hand, the law has a symbolic value that may be more important because it puts people and businesses on notice that discrimination against people who are disabled is illegal. “It is a way society conveys something about its values by passing something like this,” Dinerstein said.

Morris said it shouldn’t be up to people with disabilities to address all the violations of the law.

“I think a lot of disabled people, myself included, at some point, you grow tired of fighting,” said Morris, 30, of Orlando. “Even some of the most basic accessibility that should exist, the law says should exist, that has been regulated for (30) years — when it doesn’t exist, we have to perform a risk-reward calculation on our time. No one gets paid to be an advocate. It’s a volunteer activity that we are doing for ourselves and our community.”

Morris said he sees violations all the time when he’s out in the community. “I don’t have the time or the bandwidth to write in about all of those. All of this work takes an awful amount of time for disabled people.”

Karin Davis-Thompson, who has a disabled daughter, said the ADA “at least gives people with disabilities some protection and a place to go when they are mistreated.” But she added, “Honestly, there is still a lot of work to be done. I sometimes feel that while organizations will follow the letter of the law, they will miss the spirit of the law.”

She said she’s had to fight for information for her daughter that should have been readily available. She’s had to do her own research to find out what her daughter was entitled to and have had “several pointed conversations with the school district” to ensure school officials were following the law.

Davis-Thompson, 47, of Riverview, FL, writes a blog about the struggles of being African-American with a special needs child. She said she’s even had to fight for her niece after she had shoulder surgery and her teachers failed to accommodate her needs.

ADA evolves over time

The law was written in a way that allows it to evolve with each court decision interpreting its meaning and application, according to Peter Blanck, university professor at Syracuse University and author of a new book Disability Law and Policy.

The courts are continually interpreting the law. And businesses reach settlement agreements under the law that establish its requirements for others.

In June, for example, Lyft, the ride sharing service, reached a settlement with the federal government over allegations its drivers were not giving rides to people with foldable wheelchairs. The company agreed not to exclude people with disabilities from its transportation services and to require drivers to help stow foldable mobility devices used by people with disabilities.

Lyft also agreed to educate its drivers about the policy and issue quarterly reminders.

And last year, the Justice Department announced that Greyhound had paid more than $3 million in settlements to individuals with disabilities who faced discrimination while traveling or attempting to travel on the company’s buses. The company also agreed to implement a series of reforms, including reporting to the Justice Department on its compliance efforts.

Disability advocacy organizations have also gone to court to enforce the law.

For example, in 2012, the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund reached a settlement with Netflix ensuring the company would provide closed captions for all its streamed content.

The ADA has been subject to abuse

“Disability is not monochromatic,” Blanck said. “It is a fluid category. It changes over time and context. And the fact that it cuts across all other minority identities, race, gender, ethnicity, it has proved to be an easy target for criticism over the years that the law overreaches.”

Blanck conceded there have been abuses, from people who wrongly use handicapped parking placards to those who claim their pets are service animals to those who claim ADA excuses for not wearing masks during the pandemic.

There have also been lawyers who abused the law by filing serial lawsuits against businesses and forcing them to pay settlements for sometimes frivolous accessibility violations. Blanck said that issue has been overblown.

He noted that courts have sanctioned attorneys for this behavior. And he added, “I am not aware of a single small business that has been quote, put out of business because it needed to comply with the ADA,” he said. “To the contrary, I would suggest that these green dollars of individuals with disabilities are helping keep those small businesses afloat.”

Law removes barriers

But the law has been consequential for people with disabilities, removing barriers to living the way others take for granted.

“The world is a more physically accessible place,” Blanck said. And the benefits extend beyond the disabled, he added. For example, people pushing strollers can cross the street more easily because of curb cuts that have been installed because of the ADA.

Tony Lombardo, who is 68 and uses a wheelchair, remembers when he was growing up in the 50s and 60s that disabled people “were not human,” he said. “We were freaks. There was something wrong with you.”

Lombardo has a blog where people tell their stories of overcoming life’s obstacles.

The ADA, he said, “showed people that we are not that freaky. We are human beings. That was a start. And it helps going from there. And so, I am very, very grateful that it got the ball rolling.”

But barriers persist

Marilyn Golden, a senior policy analyst at the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, said some of the country remains inaccessible. But things have improved substantially, she added. Before the ADA, “If you had a family member like me who used a wheelchair, they couldn’t independently board a bus in most of the transportation systems in the United States,” she said. "But today, all or very nearly all city bus systems in the U.S. are wheelchair-accessible.”

Morris said some cities are better than others in ADA accessibility. For example, he said, “New York City public transportation has a long way to go to be wheelchair accessible. Most of the New York City subway system is not accessible,” which is a “further inconvenience to disabled people who want to participate in the community.”

The tourist areas of New York, like Times Square and Midtown Manhattan, are generally accessible, Morris said. But in the outer boroughs where people live, “accessibility is less of a priority.”

Washington, D.C., on the other hand does a good job with its accessible metro system, although there is some difficulty with taxis, Morris said. And Chicago is “making a lot of progress.”

Golden said Boston “is a good example” of a city that has made its older metro system accessible to wheelchair users.

Golden and Morris noted that public accommodations, particularly larger ones like hotels and movie theaters, have seen vast changes in accessibility since the ADA was enacted.

Employment still a challenge for people with disabilities

While the impact the law has had on accessibility in transportation and public accommodations has been uneven, but noticeable, its effect on employment is harder to discern.

Unemployment levels among the disabled remain stubbornly high, compared to the general population, and the pandemic has had a more profound effect on jobs for people with disabilities.

In June, the employment rate among working-age people with a disability was 28.4%, compared to 67.7% for people without a disability, according to data provided by William Erickson, research specialist at the Yang-Tan Institute on Employment and Disability at Cornell University.

Even before the pandemic, the employment gap between those with and without disability has been “pretty constant” over the last five years, between 42 and 43 percentage points, Erickson said. In 2018, for example, the employment rate for people with a disability was 37.8%, compared to 80% for people without a disability.

It’s difficult to compare the statistics to employment rates before the ADA was signed 30 years ago because definitions and means of measurement have changed. But researchers generally agree that the employment rate for people with disability has changed little over the years.

Hopeful signs for employment progress

However, Wendy Strobel Gower, program director at the Yang-Tan Institute, sees signs of progress starting to happen.

She pointed to a recent survey by the Kessler Foundation of college graduates from what it described as the “ADA generation.” The survey found that recent college graduates with disabilities were as likely to be employed as their peers without disabilities, with 90 percent of each group finding employment after college.

Gower said she thinks the younger generations don’t regard people with disabilities as scary or intimidating as past generations may have. That’s because children have been better integrated into mainstream schools than they used to be.

Gower said this has been beneficial both for the children with disabilities and their peers, who may have become more comfortable hiring them and working as colleagues.

“I have a disability,” Gower said. “I’ve worked every day of my life, and I graduated college. ... Some days are more difficult than others, but I’m very productive and I do good work.”

“Picture isn’t great” for unemployed disabled people

Still, she acknowledged that employment issues have persisted for a long time.

“A lot of people with disabilities are either not working or disenfranchised to the point that they’re no longer associated with the labor market,” she said. “The picture isn’t great.”

And violations can be nearly impossible to prove, particularly when it comes to hiring decisions. No savvy employer is going to tell a rejected job candidate that their disability was the reason.

“The only thing the ADA can do is say you can’t discriminate against people with disabilities,” Gower said. “That means you can still hire whoever you perceive to be the best candidate.”

It’s difficult to prove that a disability played a role in that assessment, Gower said. “You can’t make people not believe all the assumptions they make.”

And even if rejected job candidates think they have cases, they also must assess the cost of bringing such a charge. That calculation involves more than finances and time, but also the social cost of filing a complaint. “It costs social capital to file a charge against someone,” Gower said. People consider whether bringing a complaint will make it more difficult to get another job somewhere else.

Dinerstein said such court battles in employment cases can be difficult for individuals who face long odds and a drawn-out process. Before filing a federal employment discrimination complaint, an individual must present a case to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

The EEOC rarely will pursue a case on its own. The agency will pursue what it calls “pattern and practice” cases involving large employers with widespread discrimination. More often, though, the EEOC will issue a “right-to-sue” letter allowing an individual to go to court.

And then it’s up to the individual to find a lawyer who thinks the case is good enough that they will win and be able to collect attorney’s fees.

Regulations encourage government contractor hiring disabled

On the other hand, Gower said, businesses that have contracts with the federal government have legal incentives to hire workers with disabilities. Regulations have established an “aspirational goal” for these contractors of having 7% of their workers with disabilities.

So, while the employment picture continues to be bleak, Gower said, “It’s improving. … But it’s not a snap-your-fingers-and-have-it situation.”

And although the pandemic has had a more negative effect on jobs for people with disabilities, Dinerstein said other lasting effects from COVID-19 may actually be positive. He pointed to the fact that employers have been forced to be more flexible accommodating employees, particularly in work-from-home arrangements.

This flexibility may very well help people with disabilities find employment, Dinerstein said.

With all the progress that has happened, Morris said he hopes people recognize the disability advocates who fought for recognition 30 years ago.

“I’d like to see more attention paid to those early advocates and activists who set the stage,” he said. “They would agree there’s still much work to be done.”

Contact Elaine Silvestrini at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @WriterElaineS.