Face masks are just the latest flash point to spark when the government places mandates on individuals who are quick to feel a threat to their personal freedom.

The mask debate is preceded by ire over seat belts, motorcycle helmets, toddler car seats, smoking bans and pool safety fences, just to name a few safety measures that were not embraced by all.

The struggle to strike a balance between protecting citizens and not interfering in their lives has been a constant in America during times of war and peace, health and sickness.

During World War II, many hotels, restaurants and other businesses on the East Coast from New York to Florida refused to turn off their neon lights at night, fearing they’d lose business. German submarine captains would later write that the lights, such as those that lit up the Coney Island Ferris wheel, helped guide them to the freighters and tankers they torpedoed.

Anti-mask groups protested a mask mandate in San Francisco during the influenza pandemic of 1918. A bomb was found outside the office of the city’s chief health officer. After the first four-week mask mandate expired, church bells tolled, bars offered drinks on the house and restaurants doled out free ice cream.

RELATED: Equal Rights Amendment lies in legal limbo, as decades of debate continue

RELATED: The Constitution’s ignored stepchild: the Third Amendment

At the turn of the 20th century, there was a big debate over worker safety laws limiting how many hours someone could work in a day, according to Lou Virelli, who teaches Constitutional Law at Stetson University College of Law in Florida.

In the name of product and employee safety, governments mandated a workday shorter than 10 hours.

“The argument was from employers and employees. The employees said, ‘If I want to work those longer hours, I should be able to,’” Virelli said. “In 1905 the Supreme Court said ‘it is your right to decide what your workday should look like and we will not allow the legislature to limit your choices.’ ”

Then, 30 years later, the Supreme Court took another look at the issue and said the legislatures can infringe on the hours a person works. This was during the New Deal and views on workers’ rights had changed, he said.

Virelli stressed that the current mask debate has nothing to do with the Constitution.

“People involve the Constitution more often than it applies. If you don’t like your mask, you can complain that they are not a good idea, but you don’t have a constitutional right not to wear one,” he said.

The general consensus is it’s a free country and therefore the government can’t tell citizens what to do.

“Since the invention of laws, we have been limiting people’s choices,” Virelli said. “A large part of what law does is it protects, but then it invariably infringes on other people’s limits.”

In 1905 the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the government in Johnson V. Massachusetts when a minister refused to comply with a mandatory smallpox vaccination.

“In every well-ordered society charged with the duty of conserving the safety of its members the rights of the individual in respect of his liberty may at times, under the pressure of great dangers, be subjected to such restraint, to be enforced by reasonable regulations, as the safety of the general public may demand,” the majority wrote.

Acceptance comes with time

Even as this ruling supports mandatory mask ordinances and laws, the simple fact is people don’t like being told what to do.

“I think we’re not appreciating when something new is developed or something new occurs, it’s a process” to accept it, said Lynne McChristian, senior instructor of Risk Management and Insurance at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Gies College of Business.

“Sometimes they have to get rewarded for taking steps to protect themselves,” McChristian said. For example, people can receive a credit on their insurance if they drive a safer car.

Liability is another incentive that encourages citizens to embrace inconvenient safety precautions. Many states have hard-fought laws mandating safety fences around private, residential swimming pools. Individuals didn’t want to be forced to pay for something that compromised the view of their pool and was complicated to take down and put back each time they went for a swim. But when pools are deemed “an attractive nuisance” and homeowners could be sued if a child wanders in their yard and drowns, safety fences are seen as the lesser of two evils.

As more individuals sue employers and businesses where they believe they contracted COVID-19, McChristian expects masks will become much more prevalent and accepted.

History also shows research has made the public more likely to accept safety precautions. But it’s not the first study, the 10th or even the 50th that sways public opinion. The confusing messaging about masks has slowed the acceptance, she said.

“People are saying ‘First they told us not to wear a mask. Now they are telling us to wear a mask.’ People discount information when it’s conflicting,” she said. “As we learn more, hopefully we get smarter.”

Seat belt laws

All but one state, New Hampshire with the motto “Live Free or Die,” have mandatory seat belt laws for all drivers. Many states passed seat belt laws in the 1980s, but they weren’t all well received.

Some judges vowed not to issue fines for those caught not wearing a seat belt. Conservatives sharply criticized Elizabeth Dole, a conservative and wife of Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole, who was Transportation Secretary under President Ronald Reagan for championing seat belt laws and enforcement.

Smoking bans on airplanes

Complaints of second-hand smoke largely started with flight attendants as far back as 1969. Slight progress was made in the ‘80s: Non-smoking sections were added to planes and cigar and pipe smoking was banned. A 1986 report from the National Research Council found flight attendants were exposed to as much second-hand smoke as someone who lived with a pack-a-day smoker.

Congress passed legislation banning smoking on U.S. domestic flights of less than two hours, which became effective in 1988. By 1990 the law applied to flights less than six hours long.

Ten years later, a smoking ban on all U.S.-based international flights took effect.

Motorcycle helmet laws

In the late 1960s the federal government started requiring states to establish motorcycle helmet laws in order to qualify for certain kinds of federal highway funding. By 1975 all but three states mandated helmets for motorcycle riders.

As the U.S. Department of Transportation moved to financially penalize the states without the laws in 1976, Congress revoked federal authority for penalties. Over the next two years, eight states repealed their helmet laws, and 20 states changed them to apply only to younger riders.

Congress created incentives for helmet laws in 1991, but four years later eliminated them.

Today, 18 states and the District of Columbia have universal helmet laws, and 29 states have laws covering some riders, usually people younger than 18.

Some states, such as Florida, allow motorcyclists with medical coverage of $10,000 or more to ride without a helmet.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reports that wearing a helmet reduces the risk of dying in a crash by 37 percent. Also, riders without helmets are three times more likely to sustain traumatic brain injuries in a crash.

Decades of research illustrate the effectiveness of helmets, an element McChristian cited as key to acceptance.

Virelli said safety laws for motorcycle riders seem to ebb and flow with who is elected to office.

TSA

The Transportation Security Administration was established by the Aviation and Transportation Security Act passed by Congress soon after the attacks of 9/11. President George W. Bush signed it on Nov. 19, 2001, 38 days after the attacks. The screenings brought confusion and long lines at airports, but not the anger and protests masks have provoked.

There have been numerous lawsuits against the TSA since then, many charging it limits individual rights. But most people embraced the increased security, and taking off shoes and belts in order to fly has become second nature.

Car seat laws

The first child restraint systems for cars were introduced in 1968. Tennessee was the first state to pass a child passenger safety law in 1978.

By 1985, child passenger safety laws were implemented throughout the United States requiring children under a certain age to be restrained in a child car seat, though many laws had exceptions.

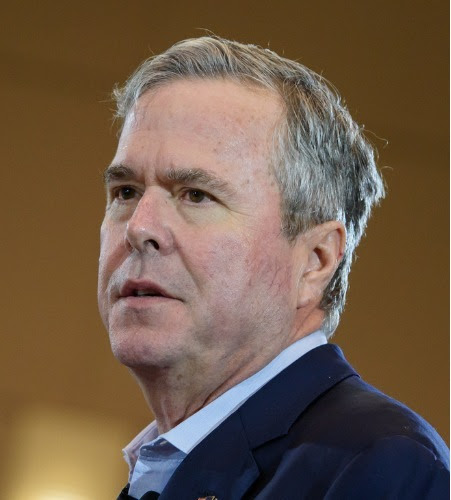

In the ‘90s, efforts began to enact state laws mandating seats for toddlers and older children. Many states and voters were against them. In 2005, for example, then-Florida Gov. Jeb Bush vetoed a bill the legislature passed that mandated booster seats for children 8 and under after they phased out of traditional car seats.

"We must not adopt policies that exalt the judgment of bureaucrats over that of moms and dads," his office said at the time. Nine years later, Florida was one of the last states to enact a law mandating a car seat or booster seat for children ages 4 or 5.

Contact Katherine Snow Smith at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @snowsmith.