As with many other things, COVID-19 is changing the face of police interviews, some say for the better.

Interviews are being conducted at a distance, frequently outdoors, to minimize the chances of virus transmission.

Suspects, witnesses and investigators are wearing masks, which may limit the ability to read facial expressions, but also encourage creative thinking and better interview techniques, experts say.

RELATED: Black, deaf Americans face extra obstacles when dealing with police

RELATED: Divorce spiking during pandemic

The changes are also accelerating the move away from old, controversial interrogation techniques that involved investigators being physically close to suspects but may have contributed to some false confessions.

Overall, police and experts say the changes are not significantly inhibiting the interview process. And they’re becoming part of a rethinking of police work spurred as well by the killing of George Floyd.

Law enforcement officials “need to embrace these changes”

“I think law enforcement nationwide needs to be engaged in uncomfortable conversations,” said David J. Mahoney, president of the National Sheriff’s Association. “We’re still in the infancy of that. Leaders in law enforcement need to embrace these changes. It’s either embrace them or get ready to get run over by them because change is on its way.”

Mahoney, who is sheriff of Dane County, WI, said his department has embraced social distancing, making greater use of outdoor interrogations. Investigators, he said, are talking to suspects and witnesses over car hoods, on front porches and in parking lots.

“We certainly do more outdoors than we have ever done,” Mahoney said. They also continue to use interview rooms and conference rooms, making sure to maintain 6-foot distances and making greater use of video recording.

Interrogation in a parking lot

In a more serious crime, Mahoney said, a suspect might be placed in the back seat of a squad car and interviewed through the window by an investigator standing outside the car maintaining a level of social distancing.

“I think every region of the country is tackling this issue independently and coming up with their own best practices, if you will,” Mahoney said.

In Clearwater, FL, police are conducting most of their witness interviews outside headquarters, often in the parking lot, to allow for social distancing.

When the crime is more serious, interviews conducted inside allow for 6-foot distancing and the wearing of masks, said Lt. Michael Walek, of the department’s criminal investigations division.

“We take every precaution,” Walek said. “One of the things we take very seriously is not spreading it.”

Law enforcement getting infected

Law enforcement officers are concerned not only with protecting the community, but also minimizing their own exposure to the virus. Police across the country have become infected.

Mahoney said a training deputy and a jail deputy in his department were put on respirators after being infected with COVID-19. The training deputy, he said, is home recovering. The jail deputy is still on a respirator.

About 80 inmates in the jail tested positive, he said. The majority are asymptomatic.

Clearwater Police Department spokesman Rob Shaw said a handful of employees there have tested positive for the virus.

At first, Walek said, the social distancing was “a little bit awkward.” But now, “As everyone transitions to wearing masks on a regular basis, it’s something we’ve learned to deal with.”

Body language information not significant

Any loss of information about suspect or witnesses’ facial expressions has not been a significant problem, Walek said. “An investigative tool is body language,” he said. “But that’s not the whole case. We look for other evidence that could also substantiate the crime.”

Losing that information “is definitely not a game changer.”

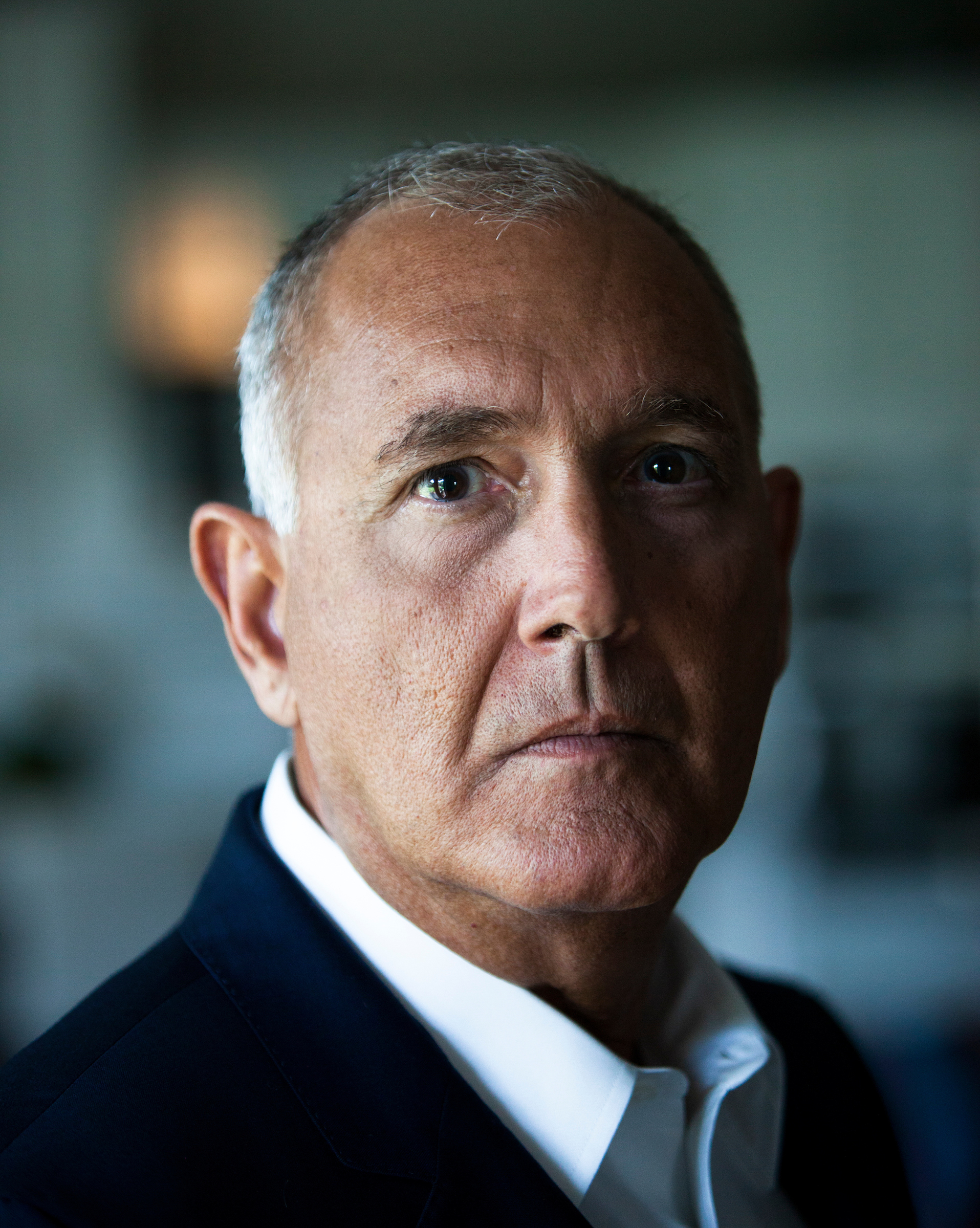

Retired FBI Agent Joe Navarro, an expert on body language, said facial expressions are a small part of body language. “For me, interviewing is about seeing the whole body,” he said.

“A lot of people out there still think really just about the face, but it’s not,” Navarro explained. “The hands reveal a lot of information. The feet reveal a lot of information. How you sit in your chair, wiggle in your chair. I would not hesitate to have an interview with someone where I’m wearing a mask and they’re wearing a mask in the same room.”

So if someone is wearing a mask while being questioned, the detective might not see that the person is licking his lips, but will still see the furrowing of the area between the eyes known as the glabella, or the tucking of the chin, Navarro said. The investigator will still hear the inflection and the cadence in the individual’s voice.

Navarro, an author of 13 books including The Dictionary of Body Language, said it’s also possible to interview via video hookup with the right camera equipment and lighting in the room with the person being questioned. High resolution cameras should be trained on the subject’s hands and feet, as well as their face.

Focusing only on the face, Navarro said, loses a lot of invaluable information.

Navarro said there are a lot of misconceptions about the use of body language by law enforcement. “People think we use body language to detect deception, and that is the biggest myth out there,” he said. “Because we don’t. First of all, you don’t convict someone by saying, well he touched his nose.

“The only thing body language does is say to you, when he answered this question, he was emphasizing, or he demurred or the question I asked caused psychological discomfort.”

Finding better ways to interview

So, while masks may block investigators from some behavioral information, Navarro said the loss is not significant. “I think it’s a minor inconvenience for a professional,” he said. “I don’t think it dampens things at all.

David Thompson, a partner in a firm that trains law enforcement in interviewing, said social distancing in police interviews is “uncomfortable because it’s different. But investigators, good investigators, are in a position where they should always be looking for what’s the most efficient, ethical way to conduct an interview.”

Thompson said his firm, Wicklander-Zulawski & Associates, has taught concepts in remote interviews for more than 10 to 15 years, focusing on telephone interviews until video interviewing was incorporated a few years ago.

The company teaches non-confrontational interviewing techniques, which Thompson said are considered better because of the possibility that confrontations will lead to false confessions, even when investigators don’t intend to intimidate.

Thompson said social distancing requirements are accelerating the change away from confrontational police interviews. “Unfortunately, a lot of practices are done because we’ve always done them that way,” Thompson said. The virus is “a shock to the system to challenge the status quo.”

Thompson said any loss in the ability to read body language shouldn’t have a negative effect. “I think there’s too much reliance on physical behavior already,” he said.

One negative, he said, may be losing some ability to read the responses of the subject to efforts by the investigator to develop rapport. But while an investigator might not be able to see a smile, the detective can consider the word selection and the sound of the voice.

Thompson said a silver lining to the virus is it is forcing police that may have used physical behavior or intimidation as a tool to focus on rapport building, on open-ended questions.

It’s become part of the rethinking of police work precipitated by social justice movements, Thompson said. “It puts a focus on, let’s challenge the training and what we’ve always done to seek information that may contradict it to make us better,” he said.

It allows investigators to focus on the interview as teamwork, being respectful of subjects, even bonding in a conversation about how uncomfortable their masks might be. “My job as the interviewer is to ask appropriate questions to let you tell your side of the story. Your job as the subject is to provide information I may not know.”

Thompson explained, “Like anything, it’s a move away from pseudo-scientific methods because it’s forcing – between COVID and the social justice movement – it’s forcing law enforcement to challenge the status quo.”

Contact Elaine Silvestrini at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @WriterElaineS.